World Countries Quiz is a free to play browser game by Michal Mrozinsky.

What does it teach?

It offers straightforward geography skill-and-drill. You will learn the names, flags and capitals of all countries in the world.

What do you do?

First choose one of the three game modes.

- Country Flags: The name of the country, its capital and its location on the map is displayed. Pick its flag from a selection of four flags with similar colors or patterns (note: could be 1 African, 1 European, 1 Asian and 1 American flag as long as they look similar).

- Country Names: The flag of the country, its capital and its location on the map is displayed. Pick its name from a selection of four neighboring countries.

- Country Capitals: The name of the country, its flag and its location on the map is displayed. Pick the name of its capital from a selection of four capitals in neighboring countries (note: not four cities of the country in question).

Then choose the continent you want to practice. You can also choose the European Union or the entire world.

“Country names” is the most obvious mode to practice. You will learn the flags and capitals there too, but it is more enjoyable to focus on the map. Each mode complements each other very well though.

If you for example choose Europe, the game will go through each of the continent’s 46 countries in turn. Their order is random but a country will never appear twice in a round.

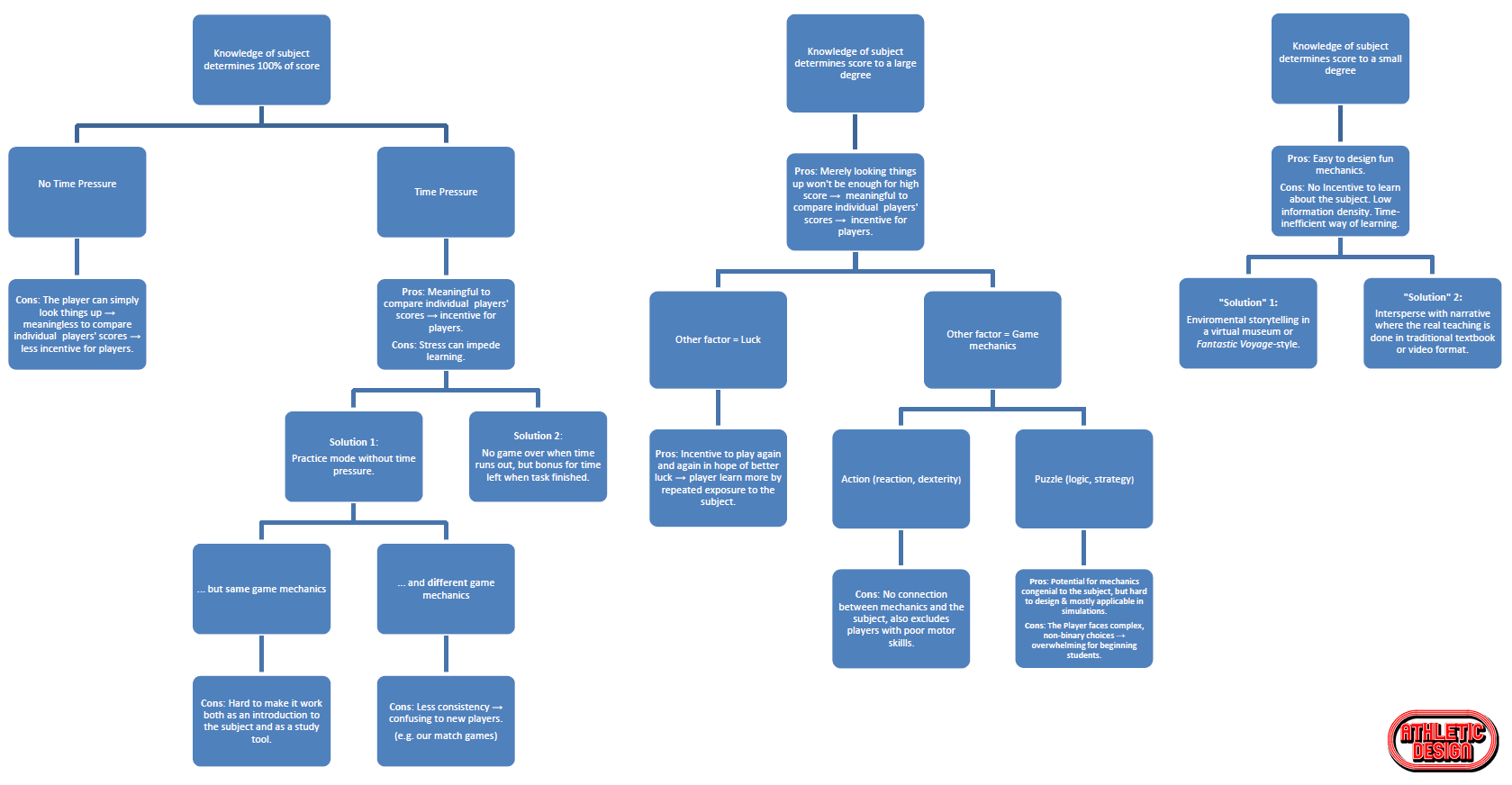

The score simply represents the percentage you get right, e.g. 42 out of 46 countries earns you a score of 91 %. You will also be given the time it took you to complete a round but it doesn’t affect your score.

Do you learn anything?

This is the kind of game were your score depends entirely on how well you know the subject being taught. It is also the kind of game where god is in the details when it comes to the design. And though by no means perfect, Michal Mrozinsky has made mostly smart design choices. You will learn; your score will improve as you learn; and you will probably find the process at least somewhat enjoyable.

While the lack of time pressure means there is no point in comparing different players’ scores, it allows you to take a good look at the map and the borders of the country you are considering. I appreciated this as I wanted to focus on geographical context rather than the (too helpful) hints offered by the flags and capitals. But I’d still welcome some additional factor that would allow for finer discrimination of scores. There could for example be more than four countries to choose from and a non-binary scoring system where bordering countries earned you half a point and non-bordering countries earned you zero.

It would also be useful if you were able to exclude the countries that you find too easy. Identifying UK, Germany, France, Italy, the Scandinavian countries and some others quickly became a minor chore when I wanted to concentrate on the Balkan countries. But to let a player customize individual parts of a game inevitably leads to interface and accessibility issues. A more sophisticated workaround would comprise a mechanic that allows the player to use the easy countries strategically the way you use obvious pieces in jigsaw puzzles and easy words in crosswords to narrow down your choices and provide clues further down the line.

Pros

A complete package: all countries in the world with flags, capitals, area and population data translated in nine languages and presented on a stylish scrolling map. Very accessible: the different modes and continents allows for individual preferences without being the least bit overwhelming. You will learn geography in a time efficient manner.

Cons

No time pressure makes global high-score tables pointless but it would have been nice if the game at least kept track of your own best scores during a session.