Unity is put to good use. The visuals and animations are slick. Still images don’t do the game justice.

Bond Breaker is a free to play browser game. It was developed by Andy Hall of TestTubeGames in conjunction with the Center for Chemistry at the Space Time Limit at University of California, Irvine.

You need to download the Unity Web Player (free) to play it. The game is also available as apps for Android and iPhone/iPad.

What does it teach?

It provides an introduction to physical chemistry. You are introduced to protons, electrons, hydrogen atoms, ions, molecular bonds, lasers, electron energy levels, heat, Van der Waals forces and muons. You never go beyond single molecules: H2– (2 protons & 3 electrons) is as big as it gets.

What do you do?

You control a proton moving around in single screens of a “nano-world”, trying to reach the goal in each screen. It is basically a variation of the ball-rolling genre which originated with (the still astounding) Marble Madness (1984); hit a popularity peak on home computers in 1986-87; was reinvigorated with Monkey Ball (2001) and more recently returned to its ancient toy roots with tilt-controlled “wooden labyrinths” for smartphones.

A novel spin on ball-rollers, is found in our free browser games Mezzy Maze and Marbles of the Amazement Park. The latter in particular exhibits some resemblances to Bond Breaker in its approach to action puzzles. Bond Breaker is not nearly as mechanically pure but neither is it a generic model of the genre with protons and electrons just substituting for, say, red and blue marbles. A modest but clever little physics-engine (that contrary to standard physics engines deals with subatomic forces but yet works much like a normal Newtonian physics engine) allows for genuinely inspired puzzles and emergent gameplay.

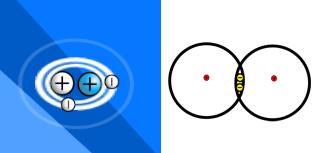

The games’ representation of molecular hydrogen (left) might confuse if you are used to the standard representation (right).

The intricacy isn’t obvious until later levels. The default levels really only fashion one long tutorial (still pretty hard to solve). But as the game provides an easy to use level editor, there is also a handful of baffling user-made levels included. And, crucially, all the physical interactions are present all the time whether a puzzle calls for them or not. You might not need to use the Van der Waals force before its formal introduction in level 17, but it has been at your disposal all the time. It might even have helped you to solve an earlier lever without you noticing.

Do you learn anything?

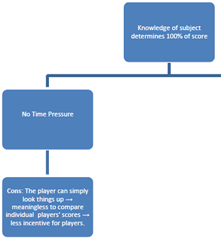

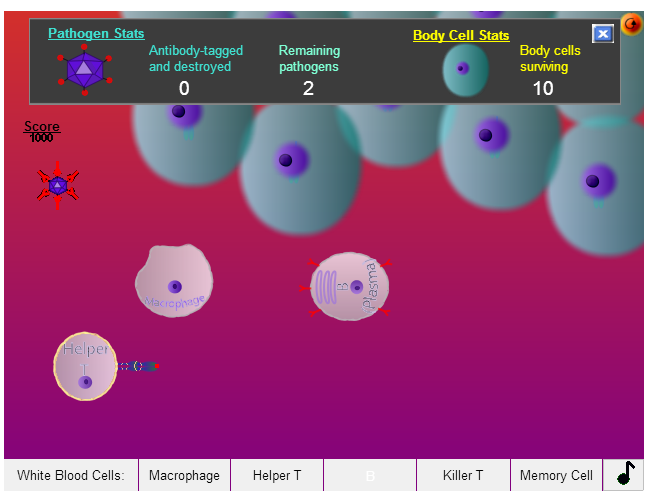

The mechanics are perfectly congenial to the subject and you will most likely solve complex levels a little faster when you have acquired a good grasp of the physical concepts. Yet Bond Breaker doesn’t quite qualify for the middle category in our educational game typology. It is too light on facts and too heavy on play. Just like rightmost category games Immune Attack, Crazy Plant Shop, Code Fred and Metablast, Bond Breaker could be labelled “broccoli covered chocolate”.

But in contrast to Code Fred and Crazy Plant Shop, the chocolate of Bond Breaker actually tastes good. And in contrast to Immune Attack, Bond Breaker doesn’t just cloak clichéd gameplay in a lab coat. The mechanics are fresh and not a natural match for any real life processes except those found in physics and chemistry.

That is to say, science has enriched the game and served as a source of genuinely novel game mechanics, but the game doesn’t enrich science or serve your understanding of it.

A win for game designer. No win for educators.

The game doesn’t really teach you anything. It might very well excite and inspire kids to look up Van der Waals forces on Wikipedia or on the games excellent companion website, but I suspect those kids will be the kids already sold on the geeky way of life. In fact I’d wager that the physics setting actually repels a lot of kids who would have enjoyed the game if atoms, ions and tunneling microscopes were replaced with hamsterballs and guns. If I’m right, the game is an educational game that doesn’t educate but only motivate – and only those already motivated…

It’s like hard Sci-Fi Novels – they often appeal to physicists but don’t generally teach you anything about physics. You wouldn’t hand over Issac Asimov’s Foundation to a fan of romance novels in hope of teaching her physics. It wouldn’t appeal to her. And even if it appealed to her it wouldn’t teach her anything about physics.

Granted, there is a lot of young people who “fucking love science” these days. But I don’t think they “fucking do”. Most seem rather to be enamoured with Science as a “being on the right side of history”-conceit: I-fucking-love-science-that-validates-my-worldview-and-political-values. And you know:

“When the cameras aren’t rolling, President Obama ponders honeybee colony collapse disorder, fusion energy, and climate change. In truth, he’s a real ‘science geek’.”

So was Kim Il-sung, I guess.

Pros

First-rate game design! Fun, original and attractive. If you like physics, you will enjoy the game all the more. And even if you don’t learn much physics, you might pick up lessons on game design by using the excellent level creator.

Cons

Will probably only preach to the choir.